the three Simones in my news feed this morning

/One Simone we’ve been talking about for weeks. One Simone just caught our national attention last night. And one Simone might be not be on your radar yet.

All three are amazing black women. All three have powerful stories. All three warrant our attention.

Let’s start with Simone Biles. She is a joy to watch, and I’m glad she’s become a household name, with her team gold and all-around medal just the start to the medals I expect she’ll bring home.

She’s creating amazing conversations too. Discussions of her adoption, including some uneducated remarks, have forced our language about adoptees and family into the news. As for her legacy, I love this quote from her: "I'm not the next Usain Bolt or Michael Phelps. I'm the first Simone Biles."

Source: CNN

But Simone Biles isn’t the only American Simone making a splash (pun intended) at the Olympics this year. By now, I expect you’ve seen the footage of Simone Manuel winning gold in the 100 freestyle in Rio. If you haven’t, please find it and watch. On the NBC broadcast, the commentators referred to her as the “other American” swimmer, as they focused back on the favorites for the race. It isn’t until the final 25 meters that they took note of Simone. And then? The look on her face when she realizes she’s won gives me goosebumps.

Source: USA Today

Simone’s blackness isn’t just a side note here. It isn’t like saying the first blue-haired swimmer won gold as part of a relay a few nights ago. (Bless your heart, Ryan.) Race matters here. In 1964, shown in the picture below, a white motel owner poured acid in his pool in an effort to scare black swimmers out of it. Before that, black actors Dorothy Dandridge and Sammy Davis Jr., in separate incidents in the 1950s, found hotel pools drained, simply because they had used them, with Dandridge merely sticking her toe in the water according to some stories. After Brown v. the Board of Education ruled that segregation in schools are unconstitutional, a federal judge decided that pools could stay separate because they "were more sensitive than schools."

Given that context, I found Simone Manuel’s words to be powerful.

“This medal is not just for me. It is for some of the African-Americans who have come before me, like Maritza, Cullen. This medal is for the people who come behind me and get into the sport and hopefully find love and drive to get to this point... Coming into this race tonight I tried to take the weight of the black community off my shoulders, which is something I carry with me...

I’m super-glad I can be an inspiration to others and hopefully diversify the sport, but at the same time I’d like there to be a day when there will be more of us and it’s not ‘Simone – the black swimmer’. The title ‘black swimmer’ makes it seem like I’m not supposed to be able to win a gold medal or break records. That’s not true. I work just as hard as everybody else and I love the sport.”

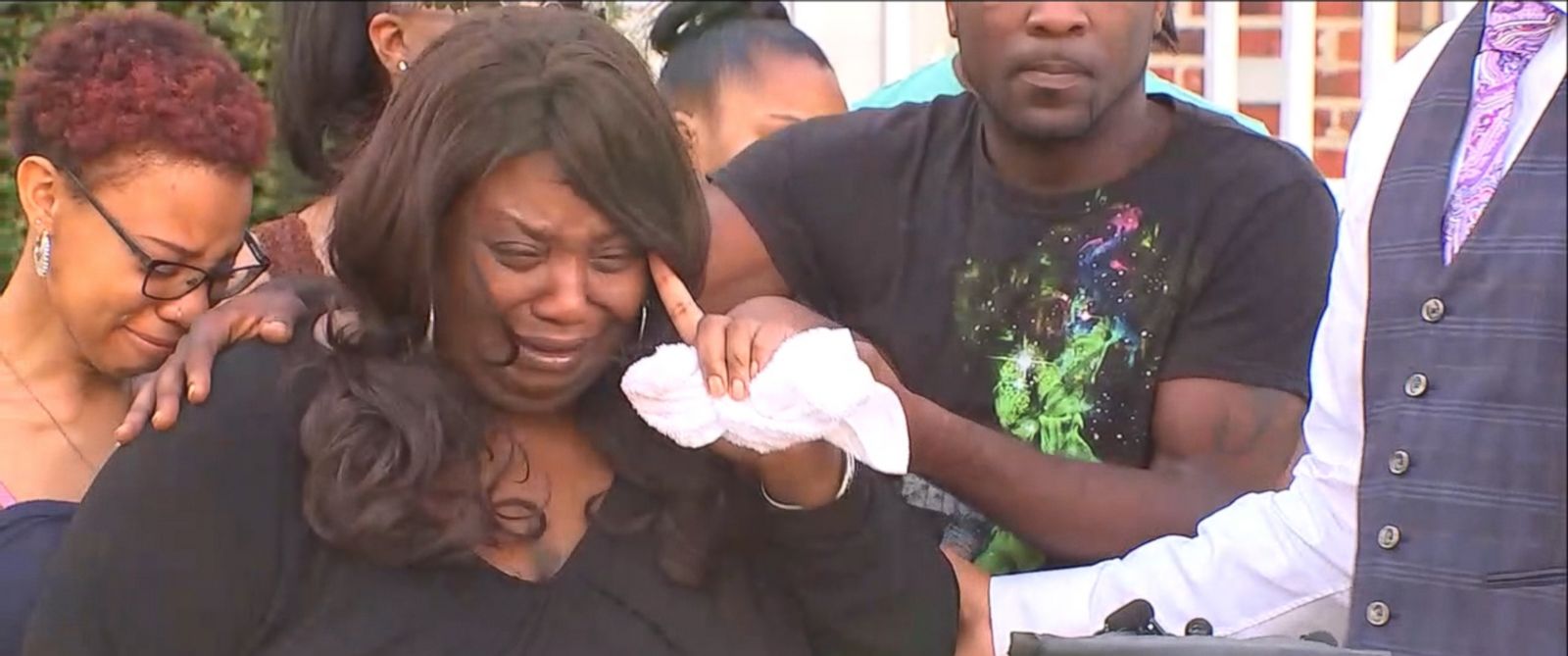

That brings me to the third Simone in my newsfeed this morning, Simone Butler-Thomas. She lives here in Raleigh. Her son, Kouren-Rodney Bernard Thomas, died this past weekend at the hands of a man who her family’s lawyer has called “Zimmerman 2.0.” You might have missed it because, sadly, an innocent black man dying has become an all too frequent story.

Source: ABC News

In Thomas's death, an officer didn’t pull the trigger. Thomas was walking home from a party. A neighbor shot from his garage, telling a 911 operator “We're going to secure our neighborhood. If I were you I would send PD.” Thomas died at the scene. Unlike many incidents in recent news, though, Thomas’s killer is in jail right now, largely I suspect because he was shot by a civilian rather than an officer.

(Let’s all remember that the movement against police brutality isn’t simply about the deaths of black people at the hands of officers but rather the lack of justice in the aftermath. When officers are killed, the act is wrong too - of course - but their killers will be charged with their crimes, found guilty, and sentenced to punishment, something which is usually not the case for black men and women when their lives are taken in incidents of police aggression. And just as I'm not criticizing all parents when I call for action against abusive ones or blasting all teachers when I demand accountability for bad ones, I - as a parent and a former teacher and the daughter of a retired police officer - am not attacking all police officers when I point out the violence by some.)

After her victory, Simone Manuel took a moment to address these hard realities.

“It means a lot, especially with what is going on in the world today, some of the issues of police brutality. This win hopefully brings hope and change to some of the issues that are going on. My color just comes with the territory.”

She wasn’t “playing the race card” – a phrase which is regularly used in attempts to silence minority voices – but rather pointing out a reality that white America is finally seeing with the spread of social media and camera phones. Police more readily use force on black Americans [1] - at a rate of 3.5 times more than whites and 2.5 more than the general population according to one study[2] and at a rate of more than twice as likely as whites according to the DOJ [3]. A detailed study from UC-Davis last year showed, from 2011-2014, that unarmed black Americans were 3.49 times more likely to be shot by police than unarmed white Americans [4].

Well, maybe black people are being more violent to warrant such a response, some suggest. But, no. A Washington Post data analysis found that "when factoring in threat level, black Americans who are fatally shot by police are, in fact, less likely to be posing an imminent lethal threat to officers at the moment they are killed than white Americans fatally shot by police." [5]. Again and again, investigations into specific areas - like Ferguson, Baltimore, Chicago, Greensboro, and San Francisco - uncover blatant racism and gross bias in policing practices. (Here's a post that examines some of these studies as well as others.)

Simply put, according to this research, my black son is more likely than my white son to be stopped, searched, met with force, arrested, charged, convicted, and sentenced harshly in the same circumstances. This reality isn't okay.

Don't get me wrong: As I see our nation celebrate Simone Biles and Simon Manuel, I cheer too. Their athletic feats and historic victories are inspiring. I’m amazed, too, by their poise and care in using their voices for others. Americans of all races and religions and backgrounds are rooting for these two Simones.

As I see Simone Butler-Thomas weep, though, I don’t see the same diversity in those who are mourning with her. When she says, “I'm going to bury my child. He was a good kid and I don’t have him no more and there’s nothing I can do,” are we hearing her? When she cries "I just want justice for my son," are we joining her in that? I’m not hearing my white friends talk about this Simone and her grief for her dead son. Why are we comfortable empathizing with Simone Biles and Simone Manuel but not Simone Butler-Thomas?

If we want to celebrate blackness in sports but turn our backs to the disparities blacks face in ordinary life, then we’re not saying they matter. We aren't. Our humanity isn’t based in our contributions, but when we wear their jerseys and celebrate their accomplishments but refuse to share in their grief, we’re saying we value their performance but not their personhood. Our language betrays us, as we claim our black brothers and sisters in victories – “we won!” as if I helped by holding my breath in suspense as I watched from my couch – but separate ourselves in sorrow – “they need to wait until all the facts are available” or, again, "they are playing the race card."

Simone Biles matters. Simone Manuel matters. They do.

But Simone Butler-Thomas matters too, and so does her son Kouren-Rodney Bernard Thomas.

Black lives matter. They do.

And I’ll keep saying it until they do to all of us, as much when they’re walking home from a neighborhood party as when they’re representing our country on an Olympic podium.